by Jacob Greenberg, Director of Recordings

2018 has been a banner year for ICE recordings, especially for Tundra, the ensemble’s in-house record label. There are now ten titles in the label’s catalog, four of which came out this year, with many more on the way. As Tundra’s director, I’d like to offer a few thoughts about the label’s present and future. And it’s especially apropos as we celebrate ICE’s records this weekend at SolstICE!

ICE started producing its own discs when we discovered the people who could help us do it. Essential to the process was Dan Lippel, ICE’s guitarist and the artistic director of New Focus Recordings. With Dan’s generosity, New Focus provided us with our first real forum for self-produced work. Our first discs on New Focus included 2008’s Abandoned Time (a program of works for guitar and ensemble), and solo albums from flutist Claire Chase and myself. In retrospect, it’s also clear that working with the amazing engineer Ryan Streber from Oktaven Audio was the key to realizing our potential as recording artists. Ryan, who first recorded us on location and then at Oktaven’s studio space in Westchester, from the start was a sympathetic partner who let us experiment during sessions, take the time we needed, and work to our own satisfaction, including many hours of attended post-production at the studio. ICE wanted the opportunity to make every new record a personal statement, which required a huge amount of time and care.

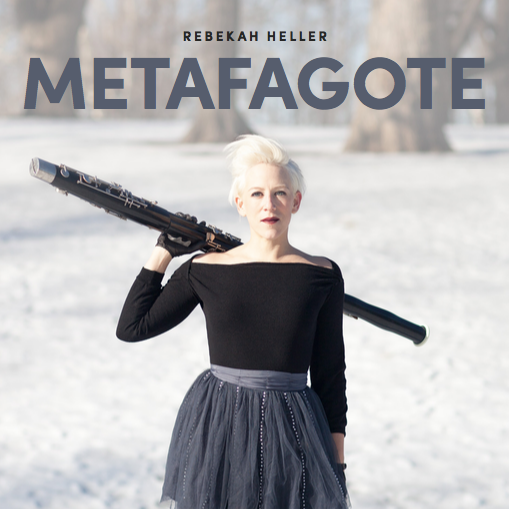

In 2013, we decided that individual members of ICE had a sizable body of commissions from composers who were closely associated with the ensemble. It seemed like a great time to put an even more personal stamp on our recordings by creating a sublabel of New Focus, our own imprint. And so Tundra was born! Rebekah Heller, our pathbreaking bassoonist (and now Co-Artistic Director), put out her 100 Names (TUN001), whose eponymous piece was written by fellow ICE member Nathan Davis. Consisting entirely of premieres, the disc set a new standard within ICE for curation and creation of material for a recording project. Rebekah not only worked with composers whom ICE had known for years, but personally commissioned all of the pieces.

More discs quickly followed, starting with Joshua Rubin’s There Never is No Light, an extremely innovative collection of pieces for clarinet and electronics. Other individuals in the group pursued their own inimitable recording projects, like saxophonist Ryan Muncy’s epic ism, and the time-traveling piano jazz of Peter Evans and Cory Smythe’s weatherbird, which started as an ICE concert at The Stone. Rebekah’s second disc, Metafagote, featured more large-scale commissions, each more astonishing than the last.

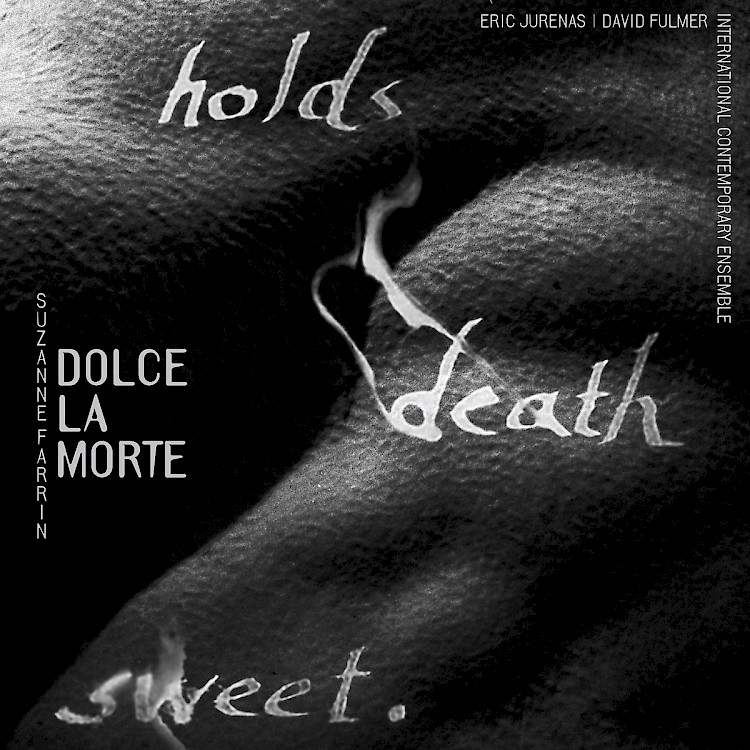

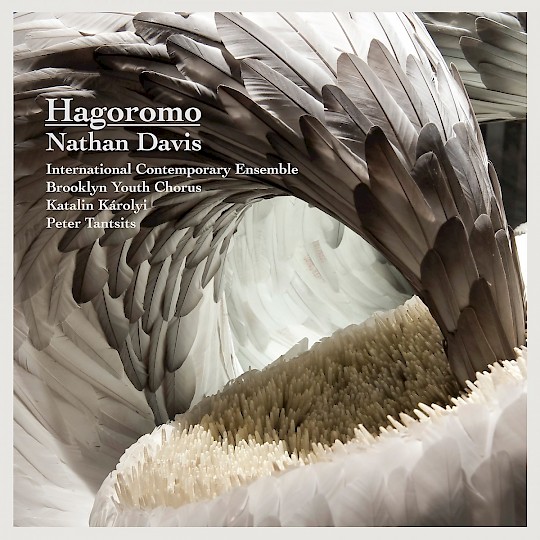

Soon, the entire ensemble joined in for large-group discs. These were centered on composer collaborations that were hatched as part of ICElab (our first large-scale commissioning project) or concert events. Marcos Balter’s Aesopica came from the first ICElab year, and George Lewis’s The Will to Adorn was based in part on live recordings from a portrait concert at Miller Theatre. Suzanne Farrin’s Dolce la Morte, one of this year’s acclaimed releases, started as another ICElab project that got its wings in workshops at Mount Tremper Arts and performances at the Metropolitan Museum. And Nathan Davis’s Hagoromo, taken from live performances at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, was ICE’s first commission through our more recent First Page program.

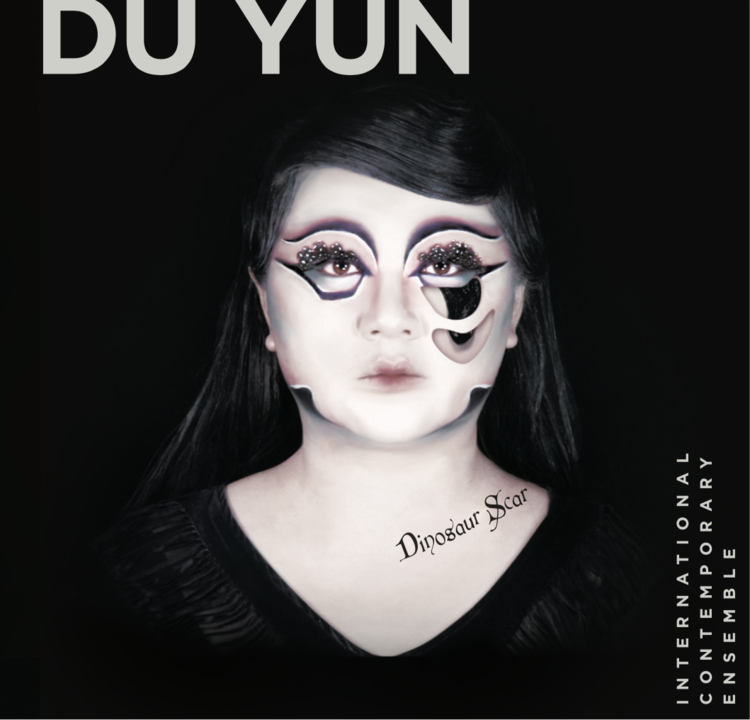

Another major release from this year, Du Yun’s Dinosaur Scar, was perhaps the longest-gestating recording project on which ICE has embarked. Five tracks from the discs (the large-ensemble works) were recorded on location as far back as 2009, with later additions of solo and smaller pieces from studio sessions. It is a panorama of ICE’s long creative relationship with Du Yun, a founding composer of the ensemble, whose work is a big part of the group’s collective DNA.

A major element of ICE’s production process is steady vetting from its members, especially in the case of large-ensemble discs. This happens also for every video that is released on DigitICE. With recording projects, which are often years in the making and dependent on grant funding, among other sources, “right of refusal” is not an option, but as Tundra’s lead producer, I always make adjustments based on member requests, from tweaking the balance in an audio mix to finding alternate takes that better represent our personnel. If a disc is composer-driven, the composer coordinates these changes, but is required to check in with the band at every important juncture.

ICE has embraced innovative methods of releasing Tundra discs, from digital-only productions to custom-made USB drives to future titles which will include video components.

For myself, record production is analogous to my working process as a performer. Collaborating closely with an engineer alongside audio software allows me to visualize and analyze the structural outline of a piece of music, while—importantly—not considering anything as fixed. Music must always have a sense of being dynamic, no matter how much we think we know a piece, and one can retain this impression of spontaneity even when crafting a permanent object like a recording. Especially with a brand-new commission, the process of creating a record is a path to the discovery of the music’s potential. Likewise, the discerning assembly work of mapping edits for a disc is like putting together a puzzle where neither the shapes of the pieces nor the final form is prescribed. It is what we make it, and ICE wants our recordings to seem intuitively right, personal, and reflecting the depth of the creators’ vision.